Character comes first

Remington Weld Philanthropy in Perspective

Positively giddy over the Virginia Cavaliers once-every-thirty-five-year-run to the Final Four, I cannot resist saying a little something about college hoops. You will likely think that I am forcing a pass into the low post here, but it really is my contention that you can learn more than a little about systems thinking by watching a game of Virginia Basketball. Specifically, on the defensive end, you will see a visual manifestation of a system in which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Virginia runs, better than anyone else on the planet, a type of ‘sagging’ man-to-man defense known as the Pack Line, developed by legendary coach Dick Bennet, the father of current Virginia Coach (and legend in-the-making) Tony Bennet. Most man-to-man defenses are designed to limit ball movement and force turnovers with intense pressure both on and away from the ball. The idea is to lock up the ball handler and deny him clear passing lanes in order to force a bad pass or contested jump shot. In such a system, you are pretty much on an island with your designated man. If he beats your pressure, little help is to be found. Other players are locked up with their own men, denying the pass, and out of position to help their teammates. Offenses that can break on-ball pressure will find it easy to drive to the basket for a high-percentage shot.

Contrast this with the way Virginia plays defense: At all times, one defender pressures the player with the basketball while four defenders position themselves inside an imaginary line 16 feet from the rim (about 3-feet inside the 3-point line). This is the Pack Line. When the ball is passed around the perimeter, the next defender closes out with high hands to prevent the rhythm shot and then provides on-ball pressure while the defender who was playing on-ball defense falls back within the Pack Line.

The Pack Line forces players to influence ball handlers toward the middle of the floor, which is typically considered to be the most vulnerable part of a defense. But with the Pack Line, the middle is where the help is. Everything Virginia does defensively stems from this concept of middle help.

This system is vulnerable to the three-point shot, to be sure; but, because it allows for help, it is forgiving. The measure of its excellence is how well it recovers when breached at the point of attack.

There are not individual stats to measure your individual defensive performance the way you can on offense. How does one measure helpfulness? So, you need players to put aside individual ego and take pride in measures of overall team defense. Not everyone is willing to do this. You do not necessarily need McDonald’s All Americans to implement the Pack Line successfully. You need smart, unselfish players with sufficient length, athleticism and willingness to help.

To bring it back to the social sector, for many years ‘gap filling’ was seen as a legitimate role for philanthropy to play; today, it seems like so many philanthropic actors would rather score points, so to speak. They want to be Duke. But we know that complex social challenges- like basketball- can be approached effectively in different ways.

Imagine philanthropy designed to help our social systems function more like Virginia’s Pack Line, philanthropy that actively facilitates coordination among agencies and measures success in ways that reward organizations that help one another. This may very well mean funding small, nimble organizations led by men and women relatively devoid of ego. It may mean funding salaries, helping to pay such people what they are truly worth. It may mean funding the underdog. It may mean many smaller grants as opposed to a few ‘big bets.’ It will, certainly, mean long hours 'in the gym' getting to know your grantees and figuring out how they can compliment each other's play. And while it may not get you on the philanthropic equivalent of SportsCenter every night, a patient, gap-oriented philanthropic portfolio can yield immensely satisfying and impactful returns, especially for small family foundations with limited resources.

Go Hoos!

Revealed in the December 2018 Chronicle of Philanthropy are the results of a study produced by Bank of America's U.S. Trust Philanthropic Solutions group in partnership with the Indiana University Lily School of Philanthopy. The study looked at the giving habits of high-net-worth philanthropists and identified four broad challenges the wealthy cite to their charitable decision making. I found myself cheered to learn that here at Remington Weld we are set up to address all four challenges rather well, and so at the risk of appearing more than a bit self serving, I thought I would record a few thoughts here.

It may seem strange to some that this is even an issue: How can we not just know what we care about? The issue here is one of precision. Sure, we can have a vague sense of wating to 'do good' for some target population; but, once you begin to press on those intuitions you might be surprised at how hollow and thin they really are. Fortunately, here at Remington Weld we employ an unapologically philosophical approach to the point of having an actual, honest-to-God philosopher on the speed dial. Thus, we know how to get to the heart of whatever matter you put before us, and we know how to do so tactfully. It is not lost on us that they put Socrates to death for asking impertinent questions.

Generous people want to give, well, generously. But money, it is alleged, does not grow on trees, and so it is imperative that your giving practices are aligned with your investment objectives and strategies. At Remington Weld, we like financial advisors and private wealth advisors (among our favorites are Don Morgan at AB Bertstein, Joe Lumarda at Capital Group, and Greg Fulmer at Morgan Stanley). We really do. We know how to speak their language and welcome the opportunity to partner with them to help you not only to generate more wealth but also to deploy your wealth in ways that help make this world a better place.

It is difficult to find anyone in the ranks of professional philanthopy who is not championing the cause of data, analytics, measurement and evaluation related to 'impact.' I am one of them, I suppose. However, I also worry that the cult of evaluation risks burdening the social sector with the same kinds of bureaucracy and gamesmanship endemic to so many public sector interventions. To be sure it is balancing act. At Remington Weld, we work with our clients to develop monitoring and evaluation programs that are bespoke, appropriately tailored to your needs and informed by the voices of those to whom you donate and those whom they ultimately serve. Otherwise, much of it is, I regret to say, just so much brouhaha spouted by those for whom it is more important to look smart than actually be smart. We aim for the latter here.

The power dynamics intrinsic to philanthropy ensure that donors almost never get the whole picture of what their money is doing and what those to whom they donate wish their money was doing. Having Remington Weld involved can go a long way to mitigate some of these dynamics. We know how to play the role of a trusted go-between in both directions, ensuring that communication among grantors, grantees and beneficiaries remains relevant and reliable.

Recently, I was cheered to discover my nephew playing a hand-held version of the generation-defining game The Oregon Trail, a game I first played on the Commodore 64 (or maybe the Apple II? Have I sufficiently dated myself?). The objective of the game is straightforward enough: get yourself and your traveling companions from Independence, Missouri to the Willamette Valley before winter sets in (the specter of the Donner Party was never too far in the background). The game presents you with a series of fateful decisions. You initially outfit your party at the general store spending a fixed amount of money (bankers start with more, farmers with less) on oxen, clothing, food, ammunition and spare parts to repair your Conestoga wagon. Then, you choose when to depart: leave too early and there will be no grass for your oxen; leave too late and you run into winter. Along the way, you use up resources trying to generate other resources: there are opportiunities to hunt for food, which uses up ammunition; and, you can trade for supplies as you go. Game play is essentially solving a series of resource management puzzles. The health of your party depends on some things things over which you have some control, like pace and rations, and some things over which you have much less control, like the weather and broken axels.

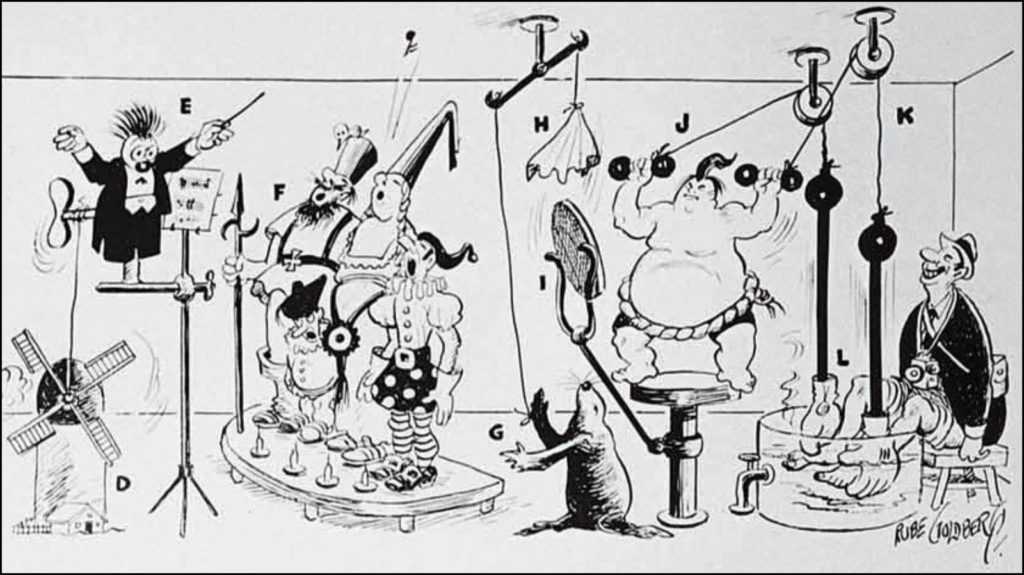

I do not play computer games anymore, perhaps to my own detriment, but I certainly make daily use of the skills I developed while playing those early computer games, which were, at their core, turn-based strategic simulations. What I did not appreciate then, but certainly do now, is the extent to which these simulations were introducing me to some of the basic ideas of systems thinking.

The term “systems thinking” can mean different things to different people. It can refer to a collection of diagnosic tools and methods, such as causal loop diagrams, for examining problems more completely and accurately before acting, allowing us to ask better questions before jumping to conclusions. It is also a "mind set" sensitive to the intrelated nature of the world in which we live. Systems thinkers are dissatisfied observing discrete events and sets of data; they challenge themselves to discover patterns. And, they look to to surface the underlying structures that explain those patterns. Once surfaced, we can then change those structures in ways that will help bring about the outcomes we desire. In the absence of systems thinking, the processes responsible for yielding those outcomes too often remain mysterious and unamenable to change.

The Systems Thinker offers (for free, courtesy of the Omidyar Group) essential works of Daniel H. Kim, Colleen P. Lannon and Barry Richmond, among other systems thinking notables, since the 1980s. I cannot recommend a set of resources more highly. Much of my own practice involves testing how far the tools and methods of systems thinking can be applying in the world of philanthropy.

Fair question(s). It cheered me recently to read good answers provided by Ann Carrns in the Wealth Special Section of the March 22, 2018 Sunday New York Times: When It Comes to Donating Money, Whom Do You Trust? It looks like her article is not behind the paywall; but, even if it is, you should probably be subscribing anyway. Hers is a great read that pretty much surfaces all the reasons why you would consider hiring someone like me to help give away your money.

If the "right side" of a logic model is concerned with impact, the left is concerned with efficiency. One way to think about efficiency is to see it as a matter of eliminating waste from a system, whether in the form of wasted materials, money or, perhaps most insidiously, time. There are a number of waste management systems (so to speak) many of which were developed with industrial production and distribution in mind. Toyota, in particular, is legendary for the waste minimization strategies it implements throughout its Toyota Production System (TPS).

Fans of Office Space will be familiar with the notion of TPS reports. What is so great about that scene in Office Space is that it illustrates what happens in an organization when ostensibly sound policies and proceedures are bureaucratized to the point that they become complicit in producing precisely the kind of inefficiency they were designed to minimize. I believe the kids call it irony. A well-functioning TPS would abhor the notion of TPS reports, much less memoranda referencing TPS reports, much less memoranda referencing cover sheets on TPS reports (If you have not seen Office Space, now would be a good time to remedy that).

The generalized version of the principles upon which TPS is based is sometimes called "lean." Over time, lean production principles have been adapted for the purposes of software development, which is a rather different endeavor than automobile manufacturing. The "Agile" framework is arguably one such adaptation, and my friend Mark LoParco has recently posted an article on LinkedIn sharing his thoughts on what he calls two "flavors" of Agile (Scrum and Kanban- do you not love these words?) I encourage you to check it out, because not only is he more than a little bit of a genius, he is an awfully good writer to boot.

This book, by Caroline Fiennes, was given to me by someone in the philanthopy game whom I very much respect right when I was starting to take the idea of philanthropic strategy seriously. It has never been out of reach since. In my previous post, I worry that I may have come across as somewhat dismissive of Logical Framework Analysis (LFA). As a tool, I think that LFA is almost indispensable. The process of subjecting ideas to such analytical rigor is rarely itself a bad idea. It is just impractical for most people who do other things than philanthropy for a living. What Caroline Fiennes manages to do in this book is give you a primer on LFA that will actually inspire you to put some of these ideas into practice immediately. It's well-written, conversational and useful. Not a bad set of adjectives.

It's not free, so before committing to the purchase you might consider this nice review in the Guardian by Michael Green (himself a very interesting cat) and this interview with the author by the Center for High Impact Philanthropy at the University of Pennsylvania.

My Canadian friends insist this is not true, but I am convinced that Canadians are by nature just a little bit better than us. After all, they gave us the great Bruce Cockburn. And Loverboy. Another case in point is Outcome Mapping (OM).

The Bible of OM was authored by Sarah Earl, Fred Carden, and Terry Smutyl in 2001. OM itself was developed by Canada's International Research and Development Centre (IRDC) to address perceived shortcomings of Logical Framework Analysis (LFA). As you will discover, the Program Monitoring and Evaluation community (PM&E, of course) has never met an acronym with which it has not fallen in love.

If you have dealt with a big foundation, especially one that has a hand in international human development, then you have undoubtedly encountered LFA-speak and its obsession with the “ballistic" term impact. People who obsess themselves with impact assessment are fundamentally skeptics. They wish the social world was more like the world of the natural sciences, a world in which we think we can know things for certain. They lament that we rarely have discrete, measurable, predictable and straightforward relationships between the programs we support through our philanthropy and the world we wish were true. OM starts from a different place, where the fact that human beings are not machines is to be celebrated. OM sees development as characterized by long-term, open problems, and accepts that 'social change' is really shorthand for many changes in many actors over a long period of time. Acknowledging that there are limits to a program’s influence, OM encourages a focus on changes the actors and organizations with which you work directly can reasonably make not only in the communities they serve but also in the ways in which they go about their work.

For most, fully implementing an OM program is too expensive and probably overkill. But, the principles on which OM is built are worth appreciating and engaging with. The good folks at the Outcome Mapping Learning Community (OMLC), a registered not-for-profit organization in Belgium, have made a trove of resources available to us. This is a rabbit hole down which you will be rewarded for diving.